The line outside Ronnie's Restaurant snaked into the Florida heat, but nobody left. They knew the rules by now: parties of three or fewer to the left, four or more to the right. Get it wrong, and a staff member would let you know about it. Ask for extra butter, and you'd be reminded, firmly, that two pats was the limit. Request a split check, and you might as well have asked for the moon.

This was Colonial Plaza in its heyday, and for 39 years, Orlandoans didn't just tolerate these indignities. They loved them.

Table of Contents

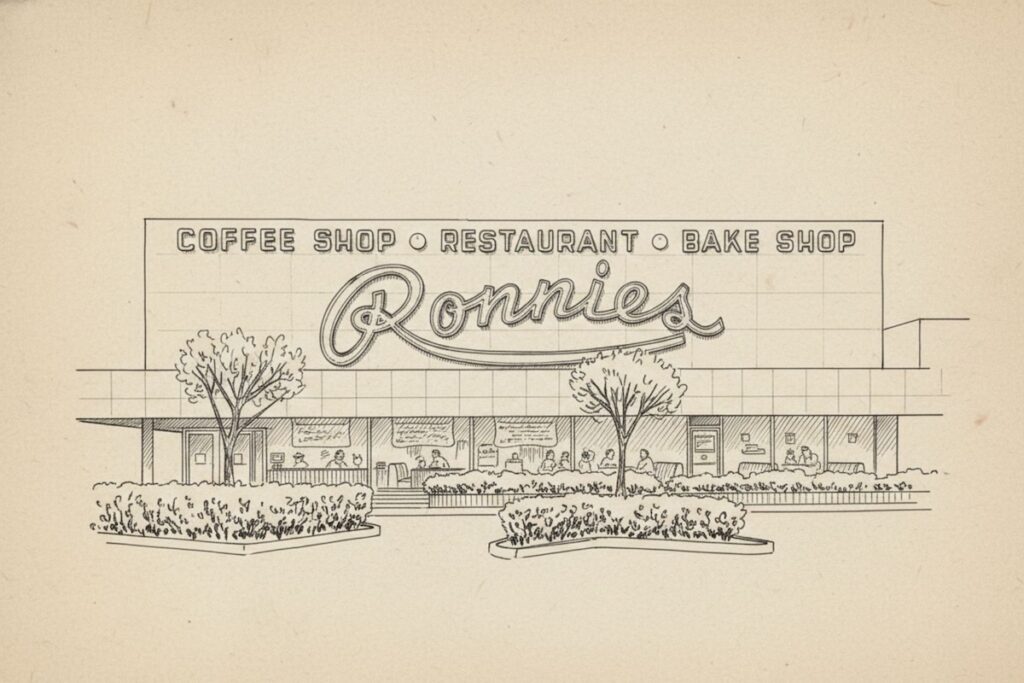

A New Yorker Opens Ronnie's Restaurant

Larry Leckart arrived in Orlando from New York City in 1955, landing in a city still figuring out what it wanted to become. That January, Colonial Plaza had just opened on East Colonial Drive as Florida's largest retail development at the time, rising from what had recently been T.G. Lee dairy pastures. An estimated 150,000 people mobbed the place on opening day, streaming in from across Central Florida to witness this strange new thing called a shopping center.

Leckart saw his moment. In May 1956, he and his wife opened the restaurant at the corner of Colonial Drive and Primrose Avenue, right in the thick of all that suburban optimism. The name carried no family significance, no deeper meaning. Ronnie's. Easy to say. Easy to remember.

What Leckart built over the next four decades would prove considerably harder to forget.

How Ronnie's Taught Central Florida to Eat

Here's the thing about Orlando in 1956: most folks had never seen a bagel. Lox was a foreign concept. Pastrami piled high on rye, matzo ball soup, blintzes, the Reuben sandwich, these weren't exotic imports from some distant land, just staples of northeastern Jewish deli culture. But for customers who'd never ventured much past Jacksonville, they might as well have arrived from another planet.

Ronnie's Restaurant became an education. Leckart wasn't simply feeding people; he was expanding palates, one corned beef sandwich at a time.

The menu sprawled well beyond deli standards into breakfast, seafood, steaks, and dishes like stuffed cabbage. But certain items achieved near-mythical status. The custard eclairs drew devotees from neighboring counties who considered the drive worthwhile for pastry alone. The Napoleons cultivated their own fierce following. And the pumpernickel onion rolls haunted customers' memories for decades after their last visit.

Then there was the Mogambo Extravaganza.

This ice cream sundae, if "sundae" even applies to something requiring two hands to carry, arrived crowned with seven flavors of ice cream and sherbet, buried under whipped cream and five different toppings. Waiters at Ronnie's ferried it through the dining room like some kind of frozen parade float while other customers stopped mid-bite to stare. The Mogambo wasn't dessert. It was theater.

Every table received a complimentary bread basket heaped with assorted rolls, pastries, pickles, and olives. Generous enough that a resourceful diner on a tight budget could fill up before the entree arrived. This wasn't an oversight on Leckart's part. The bread basket was democratic. It meant Ronnie's Restaurant belonged to everyone, regardless of what they could afford to order.

The Rules That Made Ronnie's Restaurant Famous

Other restaurants bent over backward to accommodate customers. Ronnie's Restaurant bent customers to accommodate the restaurant.

No sharing entrees. No splitting checks. Two pats of butter, and don't bother asking for more. The dual waiting lines were strictly enforced, with violations publicly corrected. Any business school professor would have called it commercial suicide.

Customers called it something else entirely: New York style. The service at Ronnie's Restaurant was brusque, borderline rude, delivered with the kind of no-nonsense efficiency that somehow felt like affection. One observer compared it to being served by your mother, if your mother had no patience for nonsense and a dining room full of hungry people waiting behind you.

Years later, when Seinfeld introduced the "Soup Nazi," longtime patrons recognized the archetype immediately. They'd been living it for decades.

The remarkable thing? None of this drove people away. Quite the opposite. The lines at Ronnie's Restaurant grew longer. The rules became legend. Customers didn't resent the strictures. They bragged about them, swapped war stories about butter denied and checks unsplit. In an era of increasingly homogenized dining experiences, the place had genuine personality. And personality, it turned out, was worth the wait.

Where Orlando Came Together at Ronnie's

The crowd defied easy categorization. Politicians passing through town, Bob Dole among them. Local celebrities rubbing elbows with working families. Businesspeople grabbing a quick lunch beside retirees who remembered when Colonial Plaza was nothing but cow pasture. Ronnie's operated as a kind of civic commons, neutral ground where Orlando's various tribes crossed paths over sandwiches and pickles.

That intersection of food and civic life reached its most dramatic moment in 1988. Mayor Bill Frederick was eating at Ronnie's when he witnessed a stabbing in the parking lot outside. Frederick sprinted to his car, grabbed his pistol, fired a warning shot, and held the attacker at gunpoint until police arrived.

It was, perhaps, the most Orlando thing that could have happened. And it happened at Ronnie's because that's simply where Orlando happened.

21 Million Customers and 4 Million Sandwiches

By the time Ronnie's Restaurant closed in 1995, it had served more than 21 million customers. The sheer volume of what passed through that kitchen staggers: 334,000 gallons of pickles, 227,000 gallons of sauerkraut, 353,000 cheesecakes, roughly 2 million matzo balls, and somewhere in the neighborhood of 4 million corned beef sandwiches.

Those numbers represent more than commercial success. They represent cultural saturation, multiple generations of Central Floridians passing through the same doors, sitting at the same tables, enduring the same rules, eating the same pumpernickel rolls. Ronnie's wasn't just a place to eat. It was a shared experience, a reference point, a landmark that belonged to the collective memory of an entire region.

The End Came Without Warning

On February 15, 1995, employees taped handwritten "closed" signs to the doors of Ronnie's Restaurant. No advance notice. No farewell tour. No last chance at a Mogambo Extravaganza. Regulars showed up for lunch and found the place simply gone.

The culprit was Colonial Plaza itself. The shopping center that had once represented Orlando's gleaming future had become its fading past. By 1994, vacancy rates hit 50 percent as enclosed malls like Orlando Fashion Square captured the traffic. Cousins/Newmarket Properties bought the property to demolish it and build a "power center," the open-air, big-box format that would define retail's next chapter.

Larry Leckart was 72 years old. He wanted to retire, play some golf, enjoy the years he'd earned. He took the buyout.

The building came down. The Leckart family auctioned what they could and donated the rest to local museums. Fragments of Ronnie's scattered into private collections and institutional archives, pieces of a whole that no longer existed.

The Legacy Ronnie's Left Behind

Colonial Plaza today is exactly what the developers envisioned: an outdoor power center anchored by national retailers. Nothing about the current configuration hints at what stood there before. No plaque, no marker, no trace of pumpernickel.

But the memory persists. The Orlando Memory project recorded oral histories from former patrons and staff. The Orlando Sentinel published Ronnie's Restaurant recipes so the devoted could attempt approximations in their own kitchens.

The nostalgia runs deeper than food. It's about a species of local institution that has grown increasingly rare: a place with genuine character, unapologetic quirks, and roots sunk deep into its community. Leckart didn't franchise. Didn't focus-group his service philosophy. Didn't care one bit whether his butter policy made sense to anyone outside the building.

For 39 years, Ronnie's Restaurant served Orlando entirely on its own terms.

Sources:

https://authenticflorida.com/ronnies-restaurant-orlando/

https://www.florida-backroads-travel.com/ronnies-restaurant.html

https://www.thehistorycenter.org/colonial-plaza/

https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1023&context=lib-rosen-exhibits

https://orlandomemory.org/places/ronnies-restaurant/

https://retrolando.com/collections/ronnies-restaurant